At Nagoya International School, the ELC (Early Learning Center) approaches education by valuing the experiences, interests, and potential of each child while empowering them to be active participants in their learning. Children are encouraged to create new understandings and knowledge with their friends and teachers. To best help children learn and explore through their experiences, NIS is inspired by the Reggio Emilia approach to support the implementation of the IB PYP curriculum and within that, often uses phrases like ‘child-centered’ and ‘inquiry-based’ as ways to describe how children are growing as learners in the ELC. But what does that mean, exactly? And more importantly, how do we know that the children are learning? How is that measured?

Taking a look into the world of the NIS ELC through the perspective of the teachers who foster the growth of dispositions, concepts, knowledge, and skills of the children, you can see how learning is nurtured and not taught. And how we document that process reveals how the children make connections and grow. Read more to discover how this learning style encourages children to continually inquire about the world around them, setting them up for a life of learning and discovery!

Documentation as a catalyst for Metacognition

As I enter the preschool space there is a quiet hum as happy children buzz around, deeply engaged in the play experience of their choice. A small group of children has been pulled into a teacher-led focus group, answering questions and developing their unit-related vocabulary. All the other children have made their personal choice by placing their names on the chart indicating where they want to spend their time.

At this point, the homeroom teacher is walking around the room, carefully watching and listening to what is happening in each area. She interacts with some children but takes her time before getting more deeply involved in what they are doing. She eventually focuses on a group of children playing with a train set and is particularly drawn in as this is the first time she has observed some of these children interacting. She observes, takes photos, and waits. Eventually, she asks one of the children: "What are you doing?" and "Who are you playing with?" She listens as the child responds.

This careful observation, followed by deliberate questioning, sets the stage for documentation. Questions are an essential part of the research to clarify the teacher's understanding of the situation. They also help develop a child’s thinking.

The next question she asks allows the child to elaborate on their explanation, "Why has it stopped?" referring to the train which has halted at the end of the incomplete track. The child explains that the track has stopped as they have come to a river. The teacher, having listened to this explanation and observed the child trying to communicate this with others, offers up an idea: "Do you want to use the water for the river?" She passes him a laminated card representing water which he willingly accepts and adds to the landscape he is creating. Here, the teacher intentionally engages with the child as a critical friend, learning and stimulating possibilities in play.

At this point, the teacher steps back, writes down transcripts of the conversations between the children, and continues to observe. She takes a variety of photographs using different angles and filters to highlight the work being done. As is inevitable when working with young people at times, disputes and miscommunication occurs, the teacher gently steps in to offer support, advice, and model: "Would you like to invite them to play?" "Do you know what happened?

While the teacher has chosen to document the learning happening in the area with the train set, she is acutely aware of the room and often checks in with other children at times having to move to different areas to support and guide other children.

Once she returns her focus to the train track group, she makes notes of who is in the space and records her hypotheses and theories around the children’s words and actions. She notices that a new child in the area is blocking the end of the track with his train as he moves it forward and backward, unsure of how to deal with the incomplete track. The teacher notices this is starting to frustrate the other children in the area who also want to move their trains along the track. She kneels close to the child and asks, "Why can’t you go?" This question allowed the child to stay within his play but problem-solve and move forward (literally and figuratively) as he proclaimed, "My train can fly!" As he lifted it into the air so that it soared off the tracks freeing up space for others. He further explained that the train was flying to Disney! Upon hearing this, the teacher again used questioning, but this time to draw other children in the area into the play as she asks, "Are you also going to Disney?" This modeling teaches the children how to incorporate each other's ideas and begin to play with one another rather than next to each other.

A moment of deep discussion and negotiation starts between two of the children. The teacher leans in closer to hear better, take photographs, and ask more clarifying questions. The children are directing the play and the teacher is there to document and stimulate when needed.

“The teachers’ role is to help children discover their own problems and questions [...] they will not offer ready solutions but instead help children to focus on a problem or difficulty and formulate hypotheses. Their goal is not so much to ‘facilitate’ learning in the sense of making it ‘smooth or easy' but rather to ‘stimulate’ it by making problems more complex, involving, and arousing.” – Carolyn Edwards, The Hundred Languages of Children (pg. 155).

During planning time the teacher begins a curating process to sort through the notes and photographs she collected so that she can document the learning. Photographs are edited and saved carefully, a title is written linked to the teacher's intention – the reason they were drawn to document this situation. In this case, it would have been easy to title the documentation around the physical act of building train tracks however, what drew the teacher’s attention were the new social interactions taking place and so the documentation piece is given the title of “Building Relationships.”

Using multiple devices the teacher curates and documents the learning journey in “Pages.” The notes are written out in greater detail, links are made to the curriculum, and quotes and photos are placed carefully so that the reader feels as though they are observing the play unfold before them. This careful documentation process takes time, and a teacher may only be able to produce three to five of these pieces each week. However, it is important to take the time to highlight the complex learning occurring in these situations so that we can evidence the rich learning that the children develop through their play.

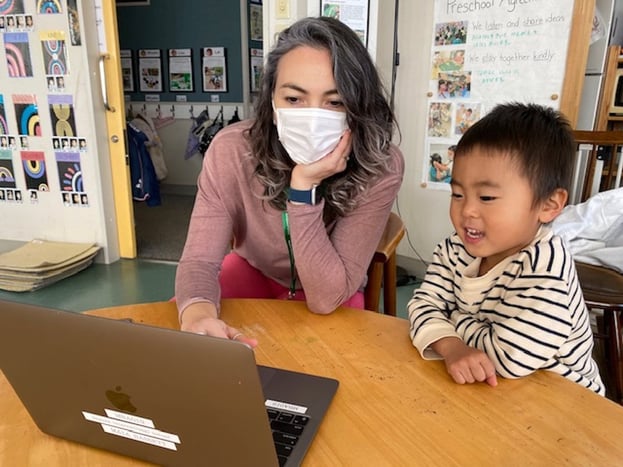

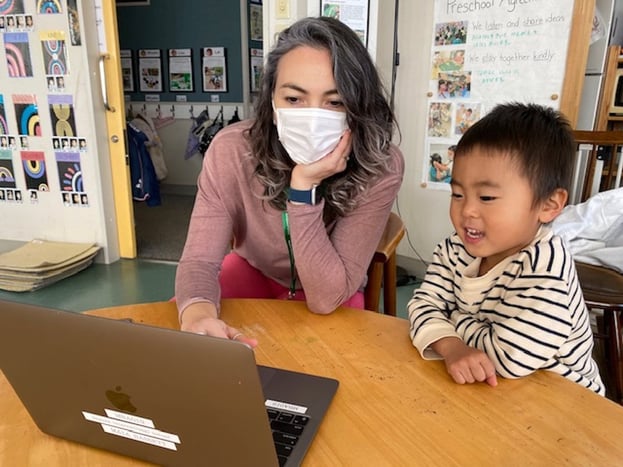

Once the teacher has compiled all of their documentation into a narrative journey we can follow, this is shared with the children. She does this to ensure that she correctly captured what happened and potential misconceptions aren't changing the true narrative. The teacher sat with the child and showed them the documentation on her computer. At the same time, she started a voice recording to capture everything the child said but remained focused on the discussion. The teacher reminded the child of what they were saying and doing in the photographs. This helped the child remember what was happening, and he naturally started adding his own explanations. The teacher prompts him to keep talking with questions such as: "Then what happened?" and "How did you feel?" The teacher adds these oral elaborations to the documentation as quotes on the photographs. At points, the teacher asked the child to consider reflective questions that not only build metacognitive skills but prompted the child to make connections between their play and the wider world. Questions such as: "Is it ok for them to come and play with you?" or "I wonder what you are telling him here?" The child was thoroughly engaged in this process and learned that we, as teachers, care for them, their experiences, and how we come to value their play. The teacher wrapped up the session by asking, "Do you want to tell me anything else?" She then thanked the child for their time.

This process is what we call pedagogical documentation because the teacher took a further step leading to an essential interaction between the child and the teacher. Making time and space for this creates an opportunity to reflect and share interpretations of personal ideas and questions about the learning experience.

This pedagogical documentation is then shared with the community in several ways – as beautiful displays for children to proudly reference, as a showcase display poster to explain our process through a unit of inquiry, or as a post to share with families on the StoryPark digital platform. One can notice as they read through documentation that it is a holistic assessment of the child rather than a snapshot of one experience, and also a collective reflection from both teacher and child. Carlina Rinaldi, president of Reggio Children in Italy and a Professor at the University of Modena, explained in her research as early as 1998 that documenting observations can stimulate a teacher’s self-reflection as well as discussions with colleagues. We feel this clearly supports our approaches regarding the essence of documentation and how it informs and nurtures learning experiences for both children and teachers.

We sincerely hope that you delight in reading and learning from the documentation our teachers so lovingly record so that we can all have a window into the wonderful learning lives of our children in the NIS ELC!